Another Article About the Neck . . . or Is It?

While the neck is a bridge, a pathway, the position of the neck and head can also indicate a multitude of other things happening beneath the surface.

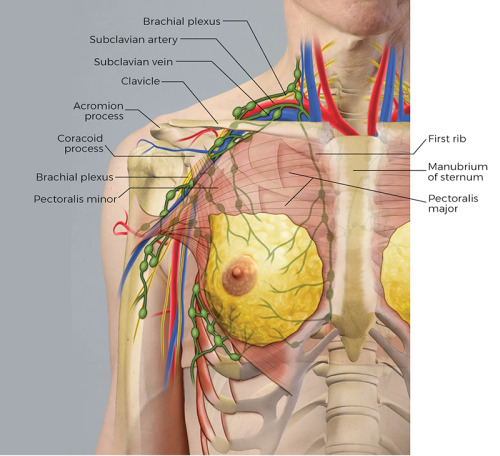

The thoracic outlet generally describes the pathway of the brachial plexus and subclavian artery and vein through the lateral neck, anterior shoulder girdle, and into the upper extremity. It is comprised of three specific regions: the interscalene triangle, located proximally; the costoclavicular triangle, located more anterior and distal; and the subcoracoid space, which is the most distal. Each region has specific anatomical features and common dysfunctions that create high potential for compression of the underlying nervous or circulatory structures.

The interscalene triangle is a narrow gap between the anterior and middle scalene muscles at the lateral neck. Both scalene muscles have attachments on the first rib, which forms the base or inferior border of the triangle. Both the brachial plexus and subclavian artery pass through this gap and are vulnerable to compression at this point. Hypertrophy or hypertonicity of the scalenes may cause significant narrowing of space between the two muscles or elevate the first rib enough to compromise the neurovascular structures contained within.

The costoclavicular triangle is located distal to the interscalene triangle and is the next area of the thoracic outlet that may become pathologically narrow. Here the brachial plexus, subclavian artery, and subclavian vein descend inferiorly, anteriorly, and laterally and must pass between the first rib and clavicle. Muscles that attach to the clavicle, such as the subclavius, pectoralis major, anterior deltoid, and trapezius, all influence the position of the clavicle relative to the first rib, as do the previously mentioned scalenes. This relative position dictates the amount of space within the costoclavicular triangle.

As they continue distally into the upper extremity, the neurovascular structures must pass deep to the anterior deltoid, pectoralis major, and pectoralis minor tendon into the subcoracoid space. This channel formed between the coracoid process superiorly, pectoralis minor tendon anteriorly, and the second through fourth ribs posteriorly is most narrow when the shoulder is fully abducted. Excessive muscle development or shortening of either the pectoralis major or minor may contribute to neurovascular compression in this region.

Compression and subsequent neurovascular compromise at any of these regions within the thoracic outlet is described as thoracic outlet syndrome. Unfortunately, this term does not distinguish which regions or structures are affected. It is not uncommon for multiple regions to be affected and symptoms consistent with neurovascular compression to increase, diminish, or alter with changes in position or activity. Symptoms vary in both quality and severity and include sensations of numbness, tingling, weakness, fullness, heaviness, and fatigue, with notable discoloration or temperature changes in the affected upper extremity.

Thoracic outlet syndrome may be caused by a variety of congenital factors, such as skeletal and muscular anomalies. Examples include the size and shape of bony landmarks like the first rib, clavicle, and coracoid process; the pathway the brachial plexus travels through the scalene muscles; and the angle and position of the pectoralis minor tendon. Acquired conditions may contribute to neurovascular compromise through the thoracic outlet. Trauma and resultant healing processes like a fractured clavicle are a common cause of thoracic outlet syndrome. Postural deviations and repetitive stress or movement patterns are also culprits, and are most successfully addressed and prevented using conservative methods like bodywork and movement education. Focus should be placed on identifying shortened soft-tissue structures like the scalene, subclavius, and pectoral muscles while addressing specific issues related to the client's posture and potentially exacerbating movement patterns.

Positioning: client supine.

Positioning: client supine.

While the neck is a bridge, a pathway, the position of the neck and head can also indicate a multitude of other things happening beneath the surface.

Understanding fibroblasts and the extracellular matrix changes how we think about the tissue we touch.

Studies reveal that 37 percent of the force generated by muscle contraction is transmitted to adjacent connective tissue structures instead of the bones.

Ongoing research suggests the sciatic nerve's healthy functioning depends on its fascial connections.