Another Article About the Neck . . . or Is It?

While the neck is a bridge, a pathway, the position of the neck and head can also indicate a multitude of other things happening beneath the surface.

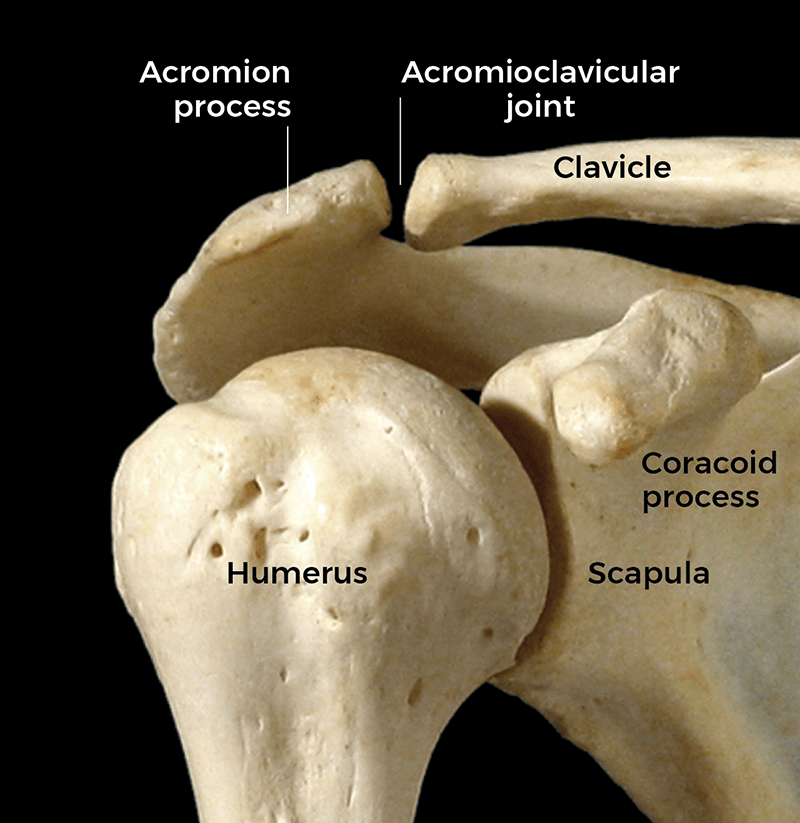

When working with clients who have a shoulder condition, our first thought might be to assess and treat the myofascial tissues across the glenohumeral (GH) joint (Image 1). The deltoid and rotator cuff muscles might spring to mind.

The idea that there is a coupling of movements between the arm at the GH joint and the shoulder girdle relative to the trunk is called scapulohumeral rhythm.

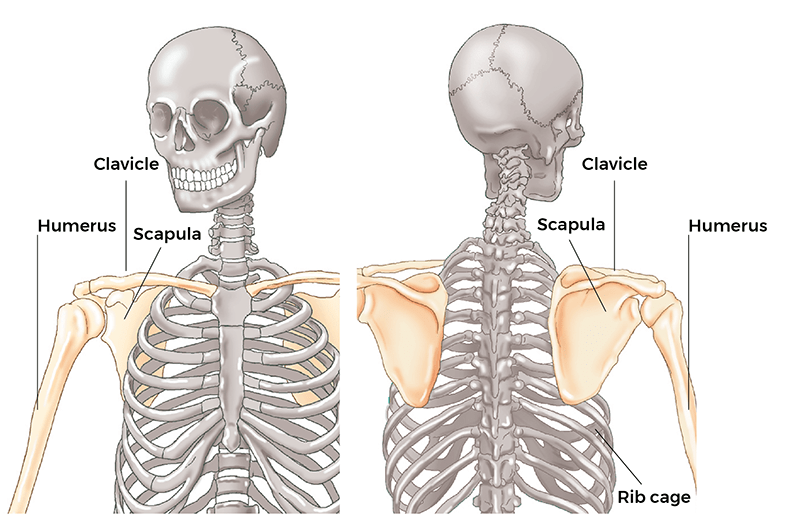

In other words, there is a rhythm between movements of the scapula and the humerus. Even though this term is excellent in that it expands our view of the functioning of the shoulder, it actually is not expansive enough. A better term for this coupled rhythm would be claviculoscapulohumeral rhythm because the clavicle also plays a crucial role in shoulder movement (Image 2). In fact, movement of the clavicle at the sternoclavicular joint may be the most underappreciated motion of the human body.

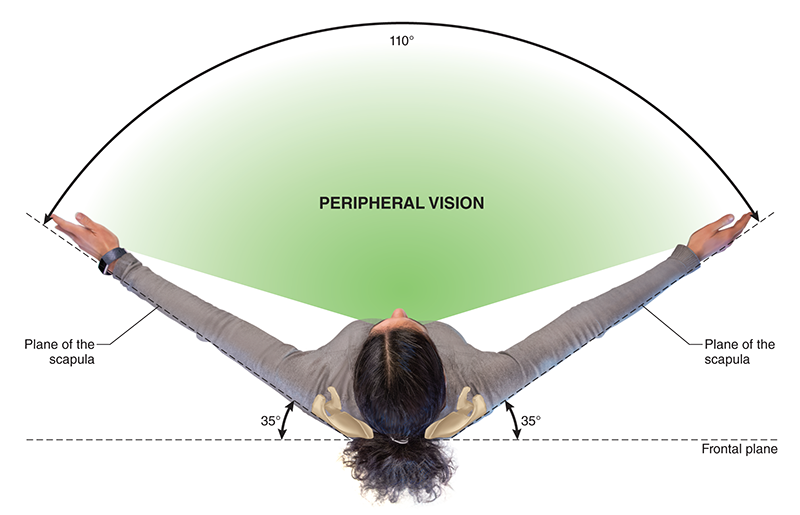

To better understand the concept of scapulohumeral rhythm, we need to appreciate the fact that the primary purpose of the upper extremity is to place the hand in the positions necessary to work with and manipulate the world. Therefore, whatever joint motions are necessary to accomplish hand placement will work in concert toward this end.

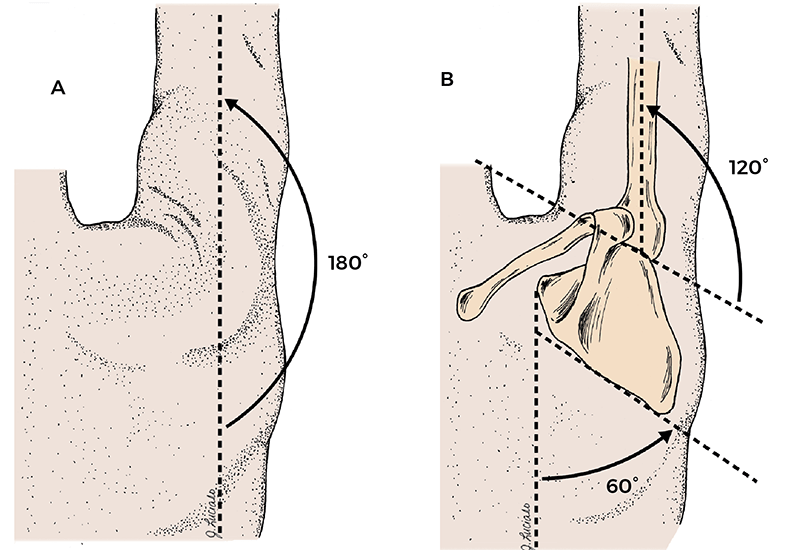

The best example of scapulohumeral coupling of motions is probably frontal-plane abduction of the arm. It is usually stated that the arm can abduct 180 degrees so that the arm is straight up in the air (Image 3A). However, the GH joint does not allow for 180 degrees of abduction. The GH joint itself allows only 120 degrees of humeral abduction, only two-thirds of the 180 degrees that is stated as full arm abduction.

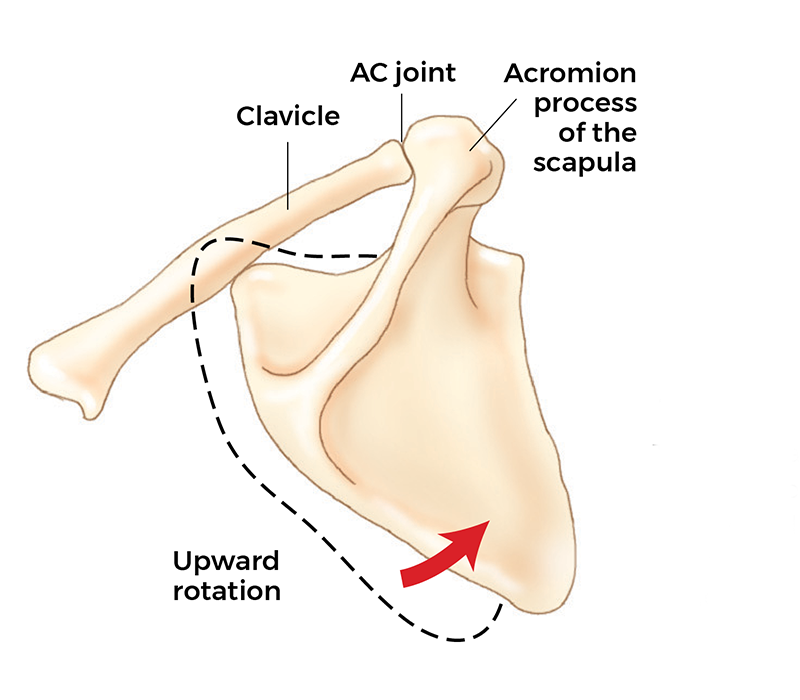

The other 60 degrees, the other one-third of this motion, is actually generated by upward rotation of the scapula relative to the rib cage of the thoracic body wall at the scapulocostal (ScC) joint (also known as the scapulothoracic joint).

Upward rotation of the scapula is a movement of the scapula at the ScC joint relative to the rib cage such that the glenoid fossa of the scapula orients upward. This affords the head of the humerus the ability to continue rolling upward until the arm is vertical at 180 degrees relative to the trunk of the body (Image 3B).

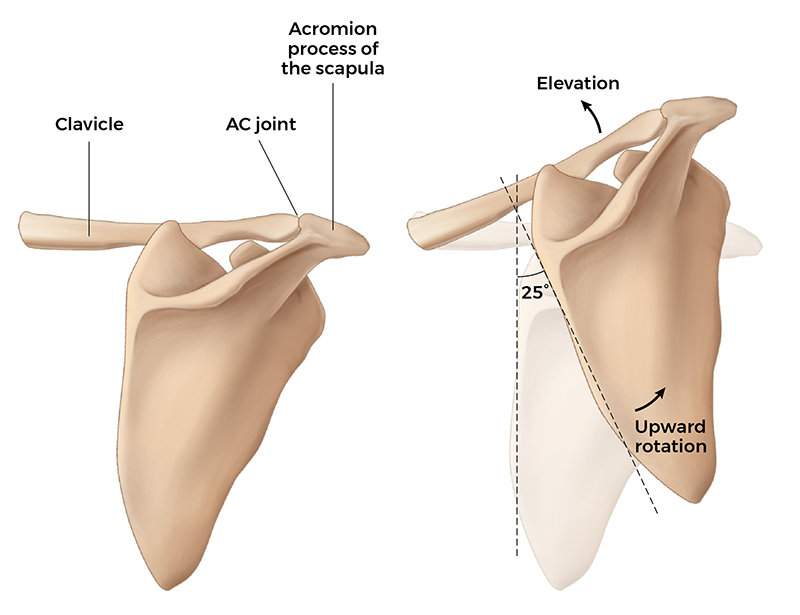

So, we see that movement of the arm/humerus is strongly dependent upon coupled movement of the scapula. But, as we have mentioned, the clavicle must be included in this conversation as well. There is a rhythm between scapular movement and clavicular movement. In fact, much of the movement of the scapula at the ScC joint is driven by movement of the clavicle. In our example of scapular upward rotation of 60 degrees to accompany full humeral abduction, half of that scapular upward rotation occurs because the clavicle elevates at the sternoclavicular (SC) joint relative to the sternum, and as the clavicle elevates, the scapula is brought along with it such that it changes its position relative to the rib cage. We could say that the scapula passively "goes along for the ride."

So, even though there are muscles that can actively move the scapula into upward rotation, the scapula can also be passively moved into upward rotation by accompanying elevation of the clavicle. For example, during the first 90 degrees of arm abduction, 60 degrees are due to GH joint humeral motion, and 30 degrees would be due to scapular upward rotation at the ScC joint.

Of these 30 degrees of scapular upward rotation, 25 degrees occur as the scapula is passively moved by clavicular motion (Image 4A). There are another 5 degrees of scapular upward rotation created by the scapula actively upwardly rotating relative to the clavicle at the acromioclavicular (AC) joint (Image 4B) (see "Scaption" sidebar and Image 5 below).

So, the question might be: Is this just anatomy geek information, or is there an application for manual therapists and movement professionals? To answer this question, let's look at a potential case study.

When we appreciate the concept of scapulohumeral rhythm, our ability to appreciate larger kinematic chains of motion increases.

A client presents with decreased abduction range of motion of the right arm. How do we perform our assessment? If we believe that all arm abduction is generated at the GH joint, then we might come to four conclusions:

This analysis might lead us toward a physical assessment of the GH joint and its myofascial tissues. However, when we broaden our scope to include scapular and clavicular motion, we realize we need to broaden the scope of our physical assessment as well.

With this broader view of shoulder function in mind, our physical assessment might expand to include the following:

*Scapular upward and downward rotation couple with clavicular upward and downward rotation respectively; scapular protraction and retraction couple with clavicular protraction and retraction respectively.

When we appreciate the concept of scapulohumeral rhythm, our ability to appreciate larger kinematic chains of motion increases. And along with this, so does our appreciation and competency of how to counsel, assess, and treat our clients not only for shoulder problems, but for all myofascioskeletal conditions of the body.

"Scapulohumeral-rhythm motion of the coupled joint actions of the shoulder joint complex that accompany frontal-plane abduction of the arm at the glenohumeral (GH) joint has been extensively studied. Following is a summation of these complex coupled actions. This level of detail is presented to manifest the beautiful complexity of scapulohumeral rhythm and illustrate the need for a larger, more global assessment of shoulder joint motion in clients who have shoulder problems.

To reiterate, full frontal plane abduction of the arm is considered to be 180 degrees of arm motion relative to the trunk. Of that motion, the arm abducts 120 degrees at the GH joint, and the scapula upwardly rotates 60 degrees at the scapulocostal (ScC) joint (with the arm "going along for the ride"); 120 degrees plus 60 degrees equals 180 degrees of total arm movement relative to the trunk. This total movement pattern can be divided into an early phase and a late phase, each one consisting of 90 degrees."

The scapula and clavicle are linked together at the AC joint as the shoulder girdle. Hence, muscular contraction that pulls and moves one bone of the shoulder girdle tends to result in movement of the entire shoulder girdle. Therefore, muscles that pull and cause upward rotation of the scapula tend to also pull the clavicle into elevation; conversely, muscles that pull the clavicle into elevation also result in the scapula upwardly rotating.

It can be seen that abduction of the arm in the frontal plane is strongly dependent on scapular movement, thus the importance of the term scapulohumeral rhythm. However, it is just as clear that the scapular motion of upward rotation is strongly dependent on clavicular motion, thus the importance of amending the term to claviculo-scapulo-humeral rhythm. Therefore, in assessment of a client with limited frontal plane motion of the arm, it is crucially important to assess not just GH joint motion but also ScC joint motion; assessing ScC joint motion then necessitates assessment of SC and AC joint motion as well. Thus, a case study of frontal-plane arm abduction truly manifests the need for healthy coordinated functioning of all components of the shoulder joint complex.

While the neck is a bridge, a pathway, the position of the neck and head can also indicate a multitude of other things happening beneath the surface.

Understanding fibroblasts and the extracellular matrix changes how we think about the tissue we touch.

Studies reveal that 37 percent of the force generated by muscle contraction is transmitted to adjacent connective tissue structures instead of the bones.

Ongoing research suggests the sciatic nerve's healthy functioning depends on its fascial connections.